By Blaise Antin, David Loevinger, Anisha Ambardar, TCW Asset Management

The shift in capital flows triggered by former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke’s tapering remarks in May 2013 set off a cascade of market events that continues to this day. His comments also birthed a cottage industry of emerging market doomsayers, who now predict regularly: 1) the end of growth in emerging markets (EM), given that it was, in their view, all a mirage fueled by carry and leverage; and 2) a wave of defaults of the kind last seen in the 1990s that threaten to bring down not only emerging but developed markets as well.

While 2013 was clearly a difficult year for emerging market assets (EM fixed income as measured by the JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified [EMBI GD] down more than 5% and EM equities as measured by the MSCI EM down almost 8%), the notion of a repeat of the crisis years that followed the Fed’s 1994 tightening – first in Mexico and then spreading in 1997-98 across the globe – seems far-fetched. The growth and balance sheet dynamics of the emerging markets have improved significantly since the 1990s as evidenced by the increase in the investment grade component of the EMBI GD from 10% to over 60% in the last decade. Moreover, there are vast differences across the emerging markets universe with only a handful of the 61 countries in the EMBI GD facing the kind of financial stress seen decades ago. Consider:

- Emerging economies now account for more than ½ of global gross domestic product (GDP), and in every year since 2005 have accounted for more than 2/3s of global growth. The IMF, in its latest forecasts, predicts that EM economies will represent slightly more than 70% of global growth in both 2014 and 2015, with EM growing more than 2 ½ times faster than DM (5.1% vs 2.0%);

EM Growth to Remain Multiples of DM Growth & The Primary Source of Global Growth

Source: International Monetary Fund

- In every year since 2000, EM economies have posted an aggregate current account surplus. This is expected to continue in 2014. And long-term foreign direct investment has accounted for the bulk of inflows, far exceeding portfolio investments;

Emerging Markets: Current Account Still In Surplus, Flows Mainly Long-Term (% GDP)

Source: International Monetary Fund, data covers all emerging markets & developing economies

- Along the way, EM countries have stockpiled 80% of the world’s foreign exchange reserves, which represent a substantial financial cushion against periods of global economic weakness or financial market upheaval;

Emerging Markets: Foreign Reserves More Than Triple Short-Term Gross External Financing Needs

Source: International Monetary Fund, data covers all emerging markets & developing economies. Gross External Financing Needs = Amortization of External Debt – Current Account Balance

- For the most part, EM sovereigns also escaped the fiscal carnage that engulfed the developed economies post-Lehman; as public debt in the developed economies jumped from around 80% of GDP in 2007 to 110% of GDP today, public debt in the emerging markets is still close to its pre- Lehman lows at 37% of GDP;

Emerging Markets: External & Public Debt Burdens and Currency Mismatches Have Fallen Significantly

External & General Govt Debt, data covers all emerging markets & developing economies. Source: International Monetary Fund.

Public debt % foreign currency: Data from 12 emerging markets which have reported data since 2006 (median). Some only report currency composition of central or general govt debt. Source: World Bank EMs have also reduced the risk of currency mismatches, both by reducing external debt (public and private) relative to exports and shifting a greater share of public sector borrowing to local currency markets; This has enabled them to move to more flexible exchange rate regimes, not only facilitating adjustments in external imbalances but also freeing central banks to focus more on price and financial stability; and

- Stronger financial regulation and supervision further contributed to much more robust financial systems.

That said, certain EMs will be challenged in a global environment characterized by a gradual normalization of U.S. monetary policy, a gradual slowing and rebalancing of Chinese growth, and the end of the commodities super-cycle. In making the negative case for emerging markets, critics generally seize upon the woes of the so-called “Fragile Five” (Brazil, India, Indonesia, South Africa, and Turkey) due to their perceived vulnerability to a reversal of global capital flows. True, each of these countries suffers from some combination of public sector and external deficits, above-target inflation, below trend growth, high credit growth, weak commodity prices, dependence on foreign portfolio flows, and upcoming elections that historically have made tough policy choices more difficult.

However, while each of the Fragile Five have real vulnerabilities, it is important to keep in mind:

- First, the fundamentals in each of these countries, while sub-optimal, are magnitudes better than during previous periods of market turbulence, and particularly the crises of the 1990s;

- Second, there are significant differences within the Fragile Five, both with respect to their overall vulnerability, areas of vulnerability, and their capacity to respond with mitigating policies;

- Third, the sell-off that started in May 2013 has already significantly re-priced the currencies and bond yields of the Fragile Five, meaning that a lot of negative news has been priced in and more competitive currencies have begun to improve trade balances; and

- Finally, the authorities in each of the Fragile Five have policy tools at their disposal to respond to market pressures and to varying degrees every member of this club has taken policy action to bolster market confidence despite the impending election cycle.

Fragile Five Changes in Real Yields Since May 2013

Source: Bloomberg

Flexible Exchange Rates Promoting a Turnaround in External Imbalances (Trade-Weighted Inflation-Adjusted Exchange Rates – Deviation from 5-year Moving Avg)

Source: Barclays Real Effective Exchange Rate Indices, Bloomberg

More policy steps are likely to be needed going forward, but the extent of the re-pricing and the policy action to date suggest that the adjustment process in the Fragile Five is underway. In fact, even as investors express concern with regard to the Fragile Five’s ability to weather changes in global capital flows there has been significant demand for new hard currency bonds issued by these countries. For example, Turkey and Indonesia have each issued $4 billion in long duration (10yr and 30yr) USD Eurobonds since the beginning of January, and have now completed the bulk of their sovereign external issuances for the year. During Q3 and Q4 of last year South Africa and Brazil issued more than $5 billion in USD Eurobonds with duration longer than 10 years. And while India does not issue external sovereign debt, foreign investment in its domestic bond market was up more than 15% in February compared to its November 2013 lows.

Looking ahead, we believe that 2014 will be a year where differentiation matters. Investors who ignore the naysayers and instead focus on the risk/reward characteristics of individuals countries through old-fashioned fundamental analysis will be well rewarded. Beyond the Fragile Five, there are many EM countries that have strong or improving credit outlooks. Given investors’ attention to the Fragile Five, in the following section we present a brief analysis of the vulnerabilities of each, how they compare now with previous periods when these countries experienced systemic crises, and the extent to which policy adjustments to date are leading to macroeconomic adjustments that will put these economies on a sounder path.

Our bottom line on the Fragile Five: Overall risk is relatively low in Brazil, moderately high in Turkey, with Indonesia and India closer to Brazil, and South Africa in the middle. In the next section, we discuss each country in order of our assessment of their vulnerability, from low to high.

Brazil

Brazil’s current ability to withstand capital outflows stands in stark contrast with the past. In the years that preceded the 1990s EM crises, Brazil reined in inflation and achieved much enhanced macroeconomic stability by adopting a prudent fiscal framework and an inflation targeting regime. It continued, however, to limit exchange rate flexibility via a de facto crawling band policy against the U.S. dollar. Exchange rate predictability encouraged borrowing, both public and corporate, in foreign currency, even in circumstances where the borrower had little foreign currency revenues. And gradual real exchange rate appreciation from relatively high inflation eroded external competitiveness. As a result, by 1999 Brazil had a current account deficit of 4.5% of GDP and net external debt that reached 38% of GDP.

Brazil: External & Public Debt Burdens Below Peaks, Foreign Currency Debt Small Share of Public Debt

Sources: Institute for International Finance, International Monetary Fund, World Bank

Brazil: Foreign Reserves Almost 2 Times Gross Short-Term External Financing Needs

Source: Institute for International Finance. Gross External Financing

Needs = Amortization of External Debt – Current Account Balance

Brazil: Rate Hikes and Currency Depreciation Promoting a Turn Around in External Imbalances

Sources: Bloomberg, Institute for International Finance

What’s different now: After more than a decade of a freely floating exchange rate, and by developing a robust local debt market, Brazil has reduced asset and liability currency mismatches substantially, with external debt to exports falling by almost half and net external debt/GDP now only 5%. Furthermore, Brazil has accumulated substantial international reserves; from 1999 to 2013, its reserves grew from USD 36 billion to USD 376 billion, making Brazil’s public sector a net international creditor and covering by almost two times its short-term external financing needs. Moreover, more than two thirds of its current account, currently at 3.7% of GDP, is financed by long-term foreign direct investments. In addition, throughout last year, Brazil remained a net recipient of portfolio investments.

There are, of course, concerns about Brazil that we do believe are valid and important to monitor. Rating agencies have signaled that a one notch rating downgrade could be warranted if the government’s fiscal performance continues to deteriorate. The proximity of Presidential elections (scheduled for October 2014) also clouds the outlook for structural reforms and fiscal adjustment. We believe, however, that Brazil will maintain its investment grade status and that further deterioration in fundamentals is unlikely. The Brazilian National Treasury is expected to announce budget cuts later this month, putting Brazil’s primary fiscal surplus close to a healthy 1.5% of GDP in 2014. Furthermore, Brazil has been ahead of the curve in addressing inflationary pressures, tightening monetary policy by 325 basis points (bps) since April 2013. The monetary policy rate is currently at 10.5%, resulting in short-term real rates of 7 ½%, among the highest in the world. We expect 75 bps of additional rate hikes, which has been already fully priced in the local yield curve. The Brazilian real has depreciated 36% since its peak in July 2011 and this will not only help restore export competitiveness, but also will reduce the imports component of locally produced manufactures. Both developments will contribute to narrowing the current account deficit, which we believe will decline to around 3% of GDP at the end of this year.

India

After growing close to 9% a year from 2005-2010, India became beset by low growth and high inflation. Growth was hampered by low tax collections, which led to large budget deficits (over 8% including state and local governments) that reduced capital available for private investment, government spending that favored subsidies over much needed infrastructure investment, and bureaucratic impediments to investments (particularly in mining and power), land acquisitions and business licenses. Inflation was boosted by monetary and fiscal policies that were kept too loose for too long after the global financial crisis and rural job and income support programs that kept rural wages and demand artificially high. By late 2012, the budget deficit, high inflation, and supply bottlenecks in key export and import competing sectors had boosted the current account deficit to over 5% of GDP, with oil and gold imports rising significantly. This left Indian rates and the rupee vulnerable, as in other countries with large external financing needs, when investors’ expectations of Fed policy shifted in May.

India: Both External & Public Debt Burdens Have Fallen Siginificantly

Source: Institute for International Finance, International Monetary Fund

India: Foreign Reserves Over 1.5 Times Short-Term Gross External Financing Needs

Source: Institute for International Finance. Gross External Financing

Needs = Amortization of External Debt – Current Account Balance

India: Rate Hikes and Currency Depreciation Promoting a Turn Around in External Imbalances

Sources: Bloomberg, Institute for International Finance

What’s different now: There are increasing signs that growth hit bottom last summer, with real GDP growth rising from 4.4% to 4.8% between the second and third quarters. Moreover, external and public debt has fallen significantly relative to exports and GDP, respectively, sovereign borrowing is entirely in local currency, and foreign exchange reserves remain ample, at more than 1.5 times short-term external financing needs (see charts). In addition, soon after taking the helm as central bank governor, Raghuram Rajan unveiled several measures to attract capital inflows, including easing restrictions on foreign investment in India’s bond market, reducing banks’ reserve requirements on foreign currency deposits, and offering currency swaps at below market rates. Furthermore, in early 2014, a commission released a long-awaited report to shift the central bank towards an inflation-targeting framework with a focus on bringing down the rise in consumer prices. Following the report’s release, the central bank hiked policy rates further, which, in our view, will help wring out still high inflationary expectations as well as boosting real incomes and private investment. Finally, higher tariffs and other restrictions have reduced gold imports significantly and, with a pick-up in external demand, cyclically weak domestic demand, and a significantly more competitive currency, it appears that the current account deficit is on a path to fall from the over 5% of GDP at the end of 2012 to an estimated 2.5% by the end of 2014.

National elections this year give some hope of improvement in India’s fiscal and regulatory constraints on growth and market sentiment. The main opposition party, the BJP, and its business friendly leader, Gujarat Chief Minister Narendra Modi, are rising in the polls, though any party winning a plurality is likely to have to assemble a governing coalition, which could include the new and populist Common Man Party. While we remain concerned about weak private investment, excessive government borrowing, and sticky inflation, we believe, at today’s elevated yields of between 8 ½ – 9%, fixed income investors are compensated for these risks with a central bank committed to bringing inflation down, growth picking up, and a rapidly adjusting trade balance.

Indonesia

The Indonesian economy has strengthened significantly since 1997 when a large current account deficit, high levels of external debt, and limited reserves all contributed to a collapse of the currency and economic growth, forcing Indonesia to turn to the IMF and restructure its debt. Since then, Indonesia has turned into one of the fastest growing major economies, with average annual growth of over 5 1/2% for the last decade. A budget law that limits deficits to 3% of GDP has kept government borrowing in check, leading to a substantial reduction in public sector debt to only 26% of GDP and a substantial reduction in external debt relative to exports. With a large endowment of natural resources, Indonesia also benefited from strong Chinese demand. However, as China’s growth has become less resource intensive, exports have weakened. Large wage increases have also adversely impacted external competitiveness in manufacturing. This, along with strong domestic demand, led to a deterioration in the current account and left Indonesia vulnerable last May.

Indonesia: External & Public Debt Burdens Have Fallen, But Large Share of Public Debt is FX Denominated

Source: Institute for International Finance, International Monetary Fund, World Bank

Indonesia: Foreign Reserves Relative to Short-Term External Needs Still Well Above Crisis Levels

Source: Institute for International Finance. Gross External Financing

Needs = Amortization of External Debt – Current Account Balance

Indonesia: Rate Hikes and Currency Depreciation Promoting a Turn Around in External Imbalances

Sources: Bloomberg, Institute for International Finance

What’s different now: Indonesian authorities have taken a series of measures to strengthen the economy. Subsidized fuel prices were increased and policy rates were hiked by 175 bps. As a result, both inflation and the trade deficit appear to have come off their peaks. Given the lag in the transmission of rate hikes to the rest of the economy, we expect credit growth and investment to slow further, bringing overall growth down closer to a still respectable 5%. The slowdown in domestic demand, along with the substantial depreciation of the rupiah should, in our view, reduce the current account deficit further.

Indonesia has a relatively young but robust democracy. Parliamentary and presidential elections are scheduled for April and July, respectively, and hold out some prospect of improved policymaking. The pro-reform, albeit relatively untested mayor of Jakarta, Jokowi, is increasingly the favorite to win the Presidency.

While the end of the commodity cycle will weigh on Indonesia’s exports and its currency, we find Indonesia’s currently elevated yields of 8-9% compelling, with inflation set to slow substantially, growth cooling to a more sustainable pace, external imbalances coming down, and the prospect of a reformist and popular new President.

South Africa

South Africa has been hit by the perfect storm over the past couple of years, as a combination of headwinds from the sharp drop in global commodity prices, aggressive labor disputes, and poor governance have taken a significant toll on the country’s economy and financial markets. Despite sluggish economic growth, options to stimulate the economy have been limited as the fiscal deficit, external and public debt, and inflation all remain relatively high. As a result, the South African rand (ZAR) has borne the brunt of the adjustment so far, depreciating more than 40% from its peak of 6.6/USD in April 2011.

South Africa: While Both External & Public Debt Burdens Have Risen, They Remain Moderate. Foreign Currency Debt Low & Falling As % of Public Debt

Source: Institute for International Finance, International Monetary Fund

South Africa: Foreign Reserves Relative to Short-Term Gross External Financing Needs Still Above Past Lows

Source: Institute for International Finance. Gross External Financing

Needs = Amortization of External Debt – Current Account Balance

South Africa: Currency Depreciation Promoting a Turn Around in External Imbalances

Sources: Bloomberg, Institute for International Finance

The South African Reserve Bank (SARB) has generally adopted a hands-off approach to currency intervention, primarily due to painful lessons it learned trying to defend the ZAR when EM currencies came under pressure in 1997- 98. Since then, South African officials have allowed the rand to float freely, and the exchange rate has served as an important shock absorber during periods of economic stress. Despite rigid resistance to outright foreign exchange (FX) intervention, SARB officials still monitor exchange rate moves closely to gauge the impact that ZAR strength/weakness might have on monetary conditions. If ZAR depreciation poses an unacceptable threat to the inflation outlook, rather than draining FX reserves, the SARB prefers to support the currency indirectly through interest rate hikes rather than draining FX reserves. As a result, South Africa’s FX reserves have seen steady growth from less than USD 5 billion in 1999, and are currently near an all-time high of USD 42 billion reached at the end of 2013. This should help assuage some fears about South Africa’s ability to meet its short-term external financing obligations.

In an indirect move to support the rand, the SARB policy board announced a 50 basis point rate hike in late January based on revised inflation expectations for the next two years. Although pass-through from ZAR weakness to CPI has been limited thus far, officials remain concerned about the potential inflationary impact of further ZAR deprecation. As a result, CPI is expected to breach the SARB’s inflation target ceiling of 6% in coming months, and peak at 6.6% towards the end of this year. While it’s too early to tell whether the recent rate hike is a one-off move or the start of a new tightening cycle, we believe the SARB is prepared to do more if the currency comes under further sustained pressure.

Although South Africa is not quite out of the woods, the SARB’s more proactive stance suggests that the bulk of the currency adjustment may have already taken place. However, a sustainable recovery from current levels will depend on South Africa’s ability to address structural challenges of sluggish growth and a wide current account deficit. Despite the 40% ZAR depreciation over the past couple of years, South Africa’s current account deficit has continued to deteriorate, reaching 6.8% of GDP in 3Q 2013. This is partly due to lower demand for South Africa’s commodity exports as the world’s major developed economies (U.S., Europe, and Japan) faced a series of shocks and growth in China downshifted to a more sustainable pace. With China’s economy stabilizing and growth in the developed world picking up, South Africa’s external accounts are poised to improve in 2014 (see chart). Indeed, South Africa recorded two consecutive monthly trade surpluses in November and December, suggesting a substantial improvement when 4Q 2013 current account data are published next month. However, strained relations between labor and business have prevented South African exporters from taking full advantage of the ZAR’s improved competitiveness. Periodic labor unrest in the mining and manufacturing sectors have often resulted in strikes that hurt economic activity and reduce South African exports. In addition to the impact on the real economy, these strikes also carry heavy political overtones as some of the large unions are competing for membership and influence ahead of the next general elections scheduled to be held on May 7.

All of these factors have combined to form a difficult political backdrop for President Zuma and the ANC as the country prepares for general elections scheduled to be held on May 7. President Zuma is hoping to win a second term in office, but there have been growing calls for his resignation – most recently from the National Union of Metalworkers (NUM), the largest mining union. Our base case scenario is that Zuma wins, but the ANC support falls below 60%. Although this environment could produce headwinds for South African asset prices in the next few months, we could see a pick-up in the second half of the year as election-related uncertainty fades.

Turkey

Turkey is the most fragile of the five due to its large current account deficit, substantial private sector external debt, and stubbornly high inflation. Escalating political tensions ahead of this year’s local and presidential elections have exacerbated negative investor sentiment. But these issues pale compared to the full-blown crisis that engulfed Turkey from 1999-2001 when inflation and interest rates skyrocketed and output plunged. In late 2002, Turkish voters elected a new center-right party (the AKP) with a broad mandate for change. In the years that followed, the AKP government’s commitment to fiscal discipline, structural reform, and financial stability (guided in the early years by IMF support and the prospect of possible EU membership in the future) profoundly improved the country’s creditworthiness. While today’s AKP has become embroiled in corruption scandals and factional infighting from time to time, the progress of the last decade has been dramatic.

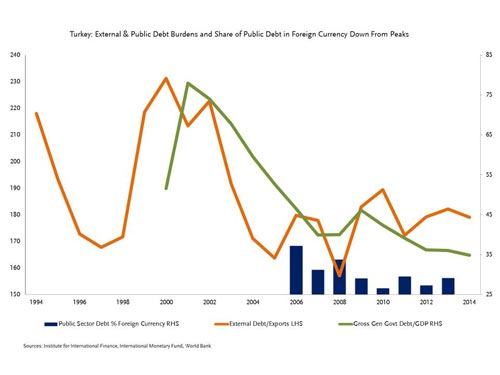

Turkey: External & Public Debt Burdens and Share of Public Debt in Foreign Currency Down From Peaks

Sources: Institute for International Finance, International Monetary Fund, World Bank

Turkey: Foreign Reserves Relative to Gross Short-Term External Financing Needs Up Slightly From Past Lows

Source: Institute for International Finance. Gross External Financing

Needs = Amortization of External Debt – Current Account Balance

Turkey: Rate Hikes and Currency Depreciation Promoting a Turn Around in External Imbalances

Sources: Bloomberg, Institute for International Finance

What’s different now: Sovereign credit metrics in 2014 are profoundly different from 2001. For example, during the past five years, which includes the Lehman-induced recession, Turkey’s fiscal deficit has averaged just 2.4% per year while public sector debt has continued to decline as share of GDP – to 35% in 2013 from 46% in 2009 (post-Lehman) and, of course, from 95% of GDP in 2001. External debt, relative to exports as well as the government’s reliance on foreign currency financing, has also dropped. And foreign exchange reserves have increased, now covering about half of short-term external financing needs.

Despite the substantial improvements during the AKP era, former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke’s initial reference to tapering last May triggered a substantial re-pricing of Turkish assets. Between end-2012 and end-January 2014, the Turkish lira (TRY) depreciated by 27% against the USD and local bond yields surged by more than 400 bps. After the lira hit an all-time low of 2.39/USD in January, the Central Bank of Turkey (CBT) announced a slew of policy changes to stabilize the currency, effectively raising rates by 225bps. Since the rate hike, TRY has traded in a 2.17-2.28/USD range, reflecting the market’s view that CBT policies are moving in the right direction.

The steep decline in the TRY and much higher local rates will inevitably contribute to important improvements in the imbalances that have made investors nervous about Turkey. The current account deficit is likely to be around 5% of GDP in 2014, down from nearly 8% in 2013 and 9-10% in 2011- 12. Inflation will surely overshoot the CBT’s 5% target this year as the lira’s depreciation feeds through to the real economy, but disinflation is likely during the second half of 2014 as domestic demand slows in response to much tighter monetary policy. While political noise will remain elevated through the nationwide local elections on March 30 and the presidential election in early summer, the outcome of the elections does not appear in significant doubt, with the AKP still favored to win key elections and maintain power. Investor confidence in Turkey’s policy capability and the competitiveness gains resulting from the weaker TRY have enabled Turkey to bring two heavily over-subscribed USD Eurobonds to the market during the first six weeks of 2014.

Conclusion

The EM sell-off, led by concerns around currencies and funding pressures, has opened up interesting opportunities, in our view. The market will continue to be subject to the uncertainty surrounding the normalization of U.S. monetary policy, but we believe that the worst is behind us at this point, with our base case tapering scenario largely priced in. While the moves in EMFX and rates in 2013 were significant, what’s notable is that they did not, as many feared, lead to currency, debt, or banking crises of the kind we saw in the 1990s, even for any of the so-called Fragile Five. To us, this reflects the progress EM countries have made in reducing their external debt/GDP, building foreign exchange reserves, moving to more flexible exchange rate systems, and improving the capitalization of and regulations governing their domestic banking systems. Looking ahead, we believe that idiosyncratic domestic events are likely to play a greater role than global factors in determining relative investment opportunities in the EM space going forward; in other words, not all countries are the same. Those countries with sound macro policies, positive growth momentum, and a commitment to structural reform are likely to present attractive carry relative to other global fixed income opportunities and some potential for spread tightening. Those countries that still suffer from high current account deficits, funded largely by portfolio investment flows, will likely continue to underperform in the absence of any substantial reforms. We would argue that such countries are the exception rather than the rule at this point, even more so now that we have already seen several of the Fragile Five take steps towards reform. In fact, in light of the depressed valuations at which their bonds are currently trading, we believe that some of these weaker credits could present interesting upside risk as they are forced by reduced global liquidity to shift to a more responsible macroeconomic policy mix.

Tags: BRAZIL, build up of foreign currency reserves, emerging market currencies, emerging markets, emerging markets analysis, emerging markets investments, emerging markets macroeconomics, fiscal responsible policies, flexible exchange rate systems, impact of normalization of U.S. monetary policy, INDIA, Indonesia, low debt to gdp, prudent monetary policy, sound macro policies, south africa, structural reforms, turkey

Oxstones Investment Club™

Oxstones Investment Club™