MONTREAL—Lined with cafes and bustling with newcomers, the streets of this eclectic port city, where French and English are spoken interchangeably, could easily be mistaken for a fashionably shabby district of Paris or Brussels.

Successive waves of immigrants—first from Europe and more recently from Asia, Haiti and North Africa—have shaped the city’s shops and restaurants, lending an international character to the vibrant downtown.

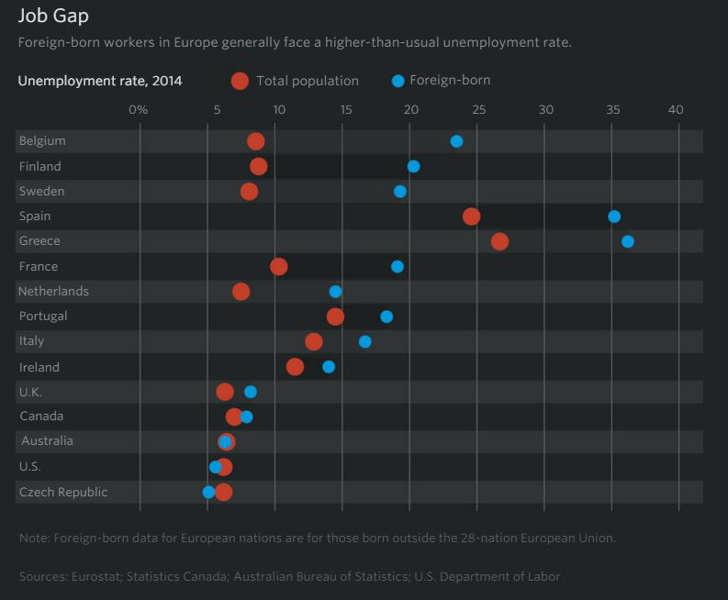

But there is a big difference. In Montreal, as in much of Canada, many of these immigrants have found full-time jobs, and their educational achievements often exceed those of the broader population. In Europe, the gap is wide. The unemployment rate among non-European citizens in the 28-member EU is 20%, double that for the population at large.

As Europe endures its biggest refugee crisis since World War II, along with the security concerns that have heightened sharply since the Paris attacks, Canada’s immigration experience may hold lessons for countries hoping to turn a demographic tide in their favor.

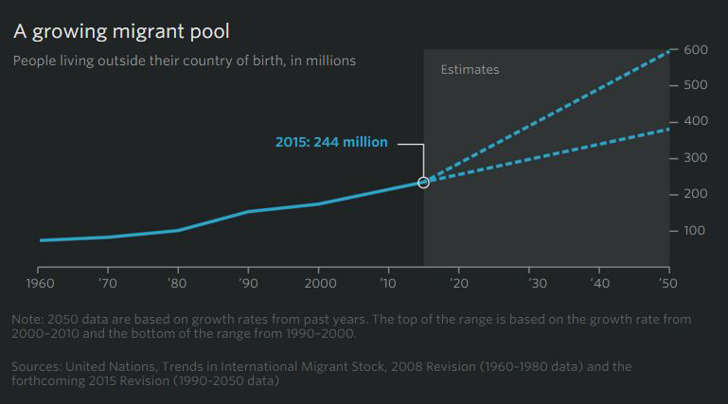

The world is on the move. There are 232 million people living outside their country of birth, according to United Nations data, the highest figure ever recorded and an increase of 57 million since 2000. By 2050, that number could go as high as 649 million, according to U.N. projections, fed by war and economic deprivation in the poorest countries with the highest birthrates.

In the big countries of Western Europe—France, the United Kingdom, Germany—12% of the population is now foreign-born. The U.S. is 14%, Canada 21% and Australia and New Zealand both above a quarter.

Those numbers mask a deep divide among rich countries. Canada, Australia and, to a degree, the U.S., have immigration policies that favor skills and promote integration, while much of Europe doesn’t. Long before this year’s epic migrant crisis began, immigrants in Europe arrived under a patchwork of programs, few geared toward seeking workers with skills.

Along with programs to bring in family members and refugees, Canada has focused on attracting immigrants with skills that will win them jobs when they arrive. Once in the country, immigrants to Canada have among the best outcomes in health, education and work in the 34-nation Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

“A big question is to what extent this result is due to the fact that Canada has a selective immigration policy or that Canada has a super-efficient integration policy,” says Jean-Christophe Dumont, head of the OECD’s international migration division. “I think probably a bit of the two.”

Article continues below video.

Canada’s experience suggests that for nations that plan ahead, migration can be an economic blessing, infusing wealthy but slow-growing populations with new blood and willing workers.

With a population of 36 million, Canada admits a quarter-million immigrants a year, one of the highest rates per capita in the developed world. New immigrants account for two-thirds of the country’s population growth, Canada’s statistics bureau estimates. Without immigration, the country’s population would eventually shrink, since the fertility rate isn’t high enough to achieve sustained growth.

A points system was established in the 1960s to help measure economic migrants’ job skills and language abilities and counter a pattern of discrimination on the basis of race and country of origin. For the past quarter century, no major political party in Canada has campaigned on an explicitly anti-immigration platform, says Irene Bloemraad, a professor of sociology at the University of California, Berkeley, who studies immigration to the U.S. and Canada.

Nafissa Abarbach landed in Montreal on a flight from Casablanca, Morocco, in January 2004, after applying and gaining entry through the economic migrant program.

Before she left the airport, Ms. Abarbach was given information about a three-day course run by the government to help new immigrants find their feet. In Montreal, a government-funded job center helped polish her résumé, and she soon found work at a pharmacy. She took night classes and became a chartered accountant, and works today as a financial controller at a Montreal printer-cartridge company, drawing a solidly middle-class salary.

The 41-year-old Ms. Abarbach, who also has relatives in France, says she believes Canada’s emphasis on attracting skilled immigrants and providing help with language and orientation eases the path for newcomers. And because the national and regional governments know ahead of time how many immigrants to expect, they are better prepared to offer them assistance when they arrive, she says.

“I arrived with experience and I restarted when I got here. I did my studies, I understand Quebec culture very well, I’ve integrated 100%,” she says one winter evening as she walked toward her downtown Montreal apartment building.

In recent years, more than 60% of newcomers to Canada arrived as economic immigrants or their accompanying family members.

Like Canada, the U.S. admits a mix of family members, employment-based migrants and refugees. However, its economic program makes up a smaller proportion of the overall immigrant mix than in Canada. Efforts to reform the U.S. system and take steps to regularize some of the country’s undocumented migrants have stalled.

The most common route to legal-resident status in Europe is “family reunification”—joining a family member who is already there. A European Union “blue card” system, established in 2009 to attract skilled immigrants, has had scant success.

Europe’s total fertility rate, an estimate of the average number of children per woman, is 1.55. Like Canada’s, at 1.61, it is dangerously below the roughly 2.1 that keeps a population stable, meaning there will be fewer working adults to support a growing number of retirees. Immigration offers a seemingly logical way to fill the gaps.

Today’s refugee crisis, along with the security concerns that have heightened sharply since the attacks in Paris and in San Bernardino, Calif., are testing the best of policies. Europe is gripped by the biggest migrant wave in over half a century: More than one million refugees and other migrants have crossed its borders this year.

Many, fleeing war and chaos, show up with few plans—and lawmakers are now struggling anew to figure out how to keep out dangerous and radicalized would-be migrants. Relatively porous borders and a continentwide zone of visa-free travel ease the way for those in search of peace and better opportunities—and potential terrorists.

But long before the attacks in Paris or the mass arrival of migrants in Europe this summer, the country in Western Europe that struggled most to integrate its immigrant population was Belgium.

The country of 11 million has large populations of Turkish, North African and Congolese descent. While the unemployment rate is 8.5%, among non-EU citizens it is 31%. It has little comprehensive policy for attracting migrants who fill needs in the labor market, nor for improving the situation of those who are already there.

“Belgium has no policy on promoting labor migration,” says Thomas Huddleston, an analyst at the Migration Policy Group in Brussels. “Like a lot of European countries,” he says, it instead “has focused on how to get fewer low-qualified people to come.”

Belgium’s largest non-European population is from Morocco, also one of the biggest recent sources of immigration to Quebec, which has favored immigrants from French-speaking countries.

In Belgium, Moroccan immigrants complain of discrimination that halts their rise in the job market.

The door to Belgium opened for many Moroccans in 1964. Needing workers for its coal mines, Belgium struck immigration treaties with a succession of countries after World War II.

The work was hard and dangerous—a mine fire in 1956 killed 262 people, many Italian immigrants—but labor was in high demand. The oil crisis in 1973 slammed the Belgian economy, and foreign workers weren’t so needed. In 1974, the immigration program ended.

By then, Moroccans had established themselves in Belgium, and more came under lenient family-reunification policies that have since been tightened.

Still others took advantage of Europe’s lax borders and came without papers at all.

Mohamed Boumediene, 27, left his hometown, Ahfir, in the eastern foothills of Morocco’s Rif mountains in 2006. He took a ferry to Spain on a tourist visa and made his way to Brussels, where an uncle lived.

“All the young people leave,” Mr. Boumediene says of Ahfir. “There are only old people there.”

In Brussels, he slipped into black-market work, doing construction and cleaning and the overnight shift at a bakery. He tried unsuccessfully to get legal-resident status in 2009, when Belgian law provided a brief window. He says he was once detained by police for working illegally, and an injury left him with medical debts he struggles to pay.

Without legal status, he is stuck: If he leaves Belgium he may never be able to return. When his younger brother toyed with joining him in Belgium, Mr. Boumediene was discouraging.

“I don’t want him to repeat the same path that I took and encounter the same suffering and sadness that I felt,” he says.

The terror attacks in Paris on Nov. 13 reinforced an anti-immigrant sentiment already rising in Belgian politics. The ringleader of the attacks was born to a Moroccan immigrant family in Belgium, and at least four of the alleged attackers lived in Brussels.

The “attacks have highlighted the necessity for a stricter screening of the foreigners coming to Belgium, and of those already present on our soil,” says a spokeswoman for Theo Francken, the Belgian state secretary in charge of migration, in a statement.

Mr. Francken’s right-wing Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie party had pushed for tighter rules, making it harder, for instance, to emigrate to Belgium to join a family member. The spokeswoman for Mr. Francken says the government acknowledged the economic disparities between migrants and those born in Belgium, and says it stemmed from “unchosen” migration of low-skilled workers. She also says the government was “stepping up its efforts to educate and integrate newcomers.”

Mr. Boumediene says the attacks heightened a charged atmosphere, which he says he sees in the police and soldiers scanning faces in the Brussels streets, and the sidelong glances in the subway. “Now, all Arabs are suspects.” He says he recently received another expulsion order from the federal government, and will ignore it as he has a half-dozen others.

Mr. Boumediene says the Belgian government needs a plan to address its population of illegal workers. “It’s not a solution to expel everyone,” he says. What is more, he says, those who fall into poverty become targets for radicalization.

“We just want to live,” he says. “We have nothing at all to do with these criminals.”

Ms. Abarbach says she is distressed by the violent attacks that have targeted civilians in recent months. She has also found it frustrating, she says, that attacks in Western countries appear to garner more of a global outcry than those that have occurred in the Middle East.

“I don’t think there’s a single true Muslim who would be happy with what’s happening—if it’s Paris, Beirut, in Syria. They’re all human beings and you have to condemn all of that,” she says.

To be sure, Canada’s geography gives it control over immigration that Europe doesn’t have: Hopeful immigrants from poorer countries can’t simply walk across a border. “We’re isolated from that, which enables us to select,” says Jeffrey Reitz, who directs ethnic, immigration and pluralism studies at the University of Toronto.

And there are concerns with the way Canada’s immigration program is run. A controversial temporary work program, which last year admitted about 95,000 people, was overhauled after allegations that Canadian employers were hiring foreign workers for low pay in order to cut wages, potentially taking jobs away from Canadians while also exploiting foreign workers.

In addition, immigrants to Canada often don’t get the jobs they are qualified to do. A 2008 Statistics Canada study found that about 60% of immigrants with university degrees were overqualified for their jobs, compared with 40.5% of their Canadian-born counterparts.

A new “express entry” system introduced earlier this year is aimed at addressing that, by placing those who meet the minimum point requirements in a short-term, ranked pool. Anyone with a job offer in Canada or interest from a regional government is moved to the top of the list. Until recently, applications were processed on a first-come, first-served basis.

It was hard for Ms. Abarbach to leave Morocco. Her family’s home is in Mrirt, a small city in the hills of central Morocco, and she went to university for biology nearby before moving to Casablanca for work. After working in a clothing factory and peddling natural products to pharmacies, she was hired by a pharmacy. The pharmacist sensed Ms. Abarbach’s ambition and encouraged her to consider going to Canada, where his daughter lived.

After consulting with her family, Ms. Abarbach enlisted the help of a Casablanca-based immigration lawyer and prepared her application. Ms. Abarbach handed over diplomas and letters from previous employers and studied textbooks on Canada and the province of Quebec, where she planned to move, to prepare for an interview with a Canadian immigration officer.

Since her departure from Morocco in 2004, two of her eight siblings have joined her in Montreal, also as economic immigrants. Her sister Saadia works as a clerk accountant at a pharmacy and studies human resources in night school, while her brother Youssef recently left a similar job to take a longer vacation in Morocco. He plans to return to school in Montreal in the New Year.

But Ms. Abarbach still feels a strong pull to Morocco. “I love Montreal, but my family is here,” she says during a visit in September to her family’s home, her first trip back in two years. “The pace is fast [in Canada] and I miss a lot of happy moments.”

One evening, Ms. Abarbach helped cook in the kitchen while her sisters, Fatima and Zahra, relaxed in Zahra’s living room.

“She made a good decision to leave,” Fatima says across a table laden with cookies and sweet mint tea. “It took a big effort for her, but we were sure she would succeed,” Fatima says. “She’s a courageous woman.”

“And ambitious,” Zahra adds from across the room.

Do they miss her?

“Toujours,” Fatima replies. Always.

Ms. Abarbach acknowledges that her transition to Canada hasn’t always been smooth. A previous Quebec government tried unsuccessfully to ban public servants from wearing head scarves and other overt religious symbols at work, which she found upsetting, even though she doesn’t wear one herself in Canada. She says she was also told to “go home” by a co-worker at one point in an earlier job.

The recent electoral victory by the Liberal Party cheered her up. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau spoke in detail about Canada’s diversity in his victory speech, and installed a diverse government: At least two cabinet members were born in Canada to immigrant parents; three more are immigrants themselves.

The new government has promised to accept 25,000 new refugees from Syria in the coming months, even as some U.S. politicians have called for a halt to refugee intakes. While concerns have been raised about how quickly the government is trying to process the new refugees, there is little substantial opposition to the broader notion of accepting a large number.

A government spokesperson declined to say how the influx of refugees might affect the number of immigrants Canada accepts through its economic and family-reunification programs.

Ms. Abarbach vows to help. She has mentored other new immigrants seeking accounting work, and is vice president of an organization that helps newcomers integrate and promotes ties between Canada and Morocco.

“If I can help one person, then why not,” Ms. Abarbach says of her volunteer work. “It’s because I’ve been through that.”

http://www.msn.com/en-us/money/markets/some-countries-see-migrants-as-an-economic-boon-not-a-burden/ar-BBnRmxt?li=BBnbfcN

Tags: canada, economic immigrants, france, Germany, Immigrants, immigrants with skills, integration policy, labor migration, refugee crisis, uk, unemployment rate

Oxstones Investment Club™

Oxstones Investment Club™