By Morgan Housel, Motley Fool,

When can you call yourself a great investor?

A reader asked the other day, “How much time do you need before you can separate skill versus luck in investing?”

My answer was “probably 20-30 years,” which he found astounding. He thought I’d say five years. But here’s my reasoning.

If a doctor performed one successful surgery, you can be pretty sure he’s an expert. If he does one successful surgery every day for a year, he clearly knows what he’s doing.

Investing is different. There are thousands of stocks, and at any given time, a fair number of them will be exploding higher. With millions of investors, some will be holding disproportionate amounts of those winners at any given moment. It can take five or 10 years of successful returns for an investor to make a case that results aren’t entirely due to chance.

But even then — with, say a 10-year track record of success — an investor can’t claim expertise. Or at least reliable expertise you’d expect from a doctor or an engineer. That’s because the world is always changing, and the true sign of a successful investor is whether you adapt and change along with it.

Bill Gross, lauded as the most successful bond investor of all time, wondered a few years ago whether his success was merely due to 30 years of falling interest rates. He wrote:

All of us, even the old guys like Buffett, Soros, Fuss, yeah – me too, have cut our teeth during perhaps a most advantageous period of time, the most attractive epoch, that an investor could experience. Since the early 1970s when the dollar was released from gold and credit began its incredible, liquefying, total return journey to the present day, an investor that took marginal risk, levered it wisely and was conveniently sheltered from periodic bouts of deleveraging or asset withdrawals could, and in some cases, was rewarded with the crown of “greatness.” Perhaps, however, it was the epoch that made the man as opposed to the man that made the epoch.

The true test of whether someone like Gross is a bond genius is whether they can keep their skill and outperformance up when the world changes, like during a 10- or 20-year period of rising interest rates. Or persistently high inflation, a surge in taxes, a world war, new regulations, or a depression. But most current managers may be long gone by then, retired comfortably on the success of the world they serendipitously spent their careers in. “Showing up at a gold rush with a shovel and a pan doesn’t make you a genius,” as one blogger recently put it.

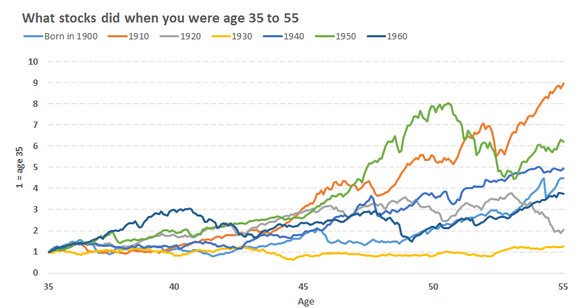

Take what stocks did from age 35 to 55. That’s the meat of a money manager’s career, the time to prove whether you’re a standout. Depending on what year you were born, stocks produced all kinds of different results:

If you were born in 1910, the market surged during the teeth-cutting part of your career, and proving yourself a star was a matter of showing up, using a little leverage, and holding on tight. If you were born in 1930, the market was a disaster during your career, and becoming a star required incredible skill and patience.

During the half-century from 1899 to 1949 – a period of two world wars — global stocks gained an average annual real return of 2.81%. From 1950 to 1999 – a period of relative calm – global stocks returned 8.53% a year.

I wonder, then, how many of the great investors of the last half-century would have fared if they born a few decades earlier?

Many would have adapted and thrived in different market environments. But some were surely one-trick ponies born in the right stable, and would have struggled to make money in a different era.

In his great book Investing, Robert Hagstrom compares financial markets to biological evolution. There’s a tendency to think of markets as something that are established and rigid — a set of numbers that get jumbled around. But they’re not. Markets evolve over time. Successful strategies are selected, while those that are no longer effective — usually because investors gain access to better information than they had before — get pushed out.

Hagstrom looked at the last 100 years, and found that four popular investing strategies have come and gone.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the discount-to-hard-book-value strategy … was dominant. After World War II and into the 1950s, the second major strategy that dominated finance was the dividend model … By the 1960s … investors exchanged stocks paying high dividends for companies expected to grow earnings. By the 1980s a fourth strategy took over. Investors began to favor cash-flow models over earnings models. Today … it appears that a fifth strategy is emerging: cash return on invested capital.

“If you are still picking stocks using a discount-to-hard-book-value model or relying on dividend models to tell you when the stock market is over or under-valued, it is unlikely you have enjoyed even average investment returns,” Hagstrom writes. You had to adapt over the years, discarding what no longer worked and figuring out what would work next.

The real mark of an expert investor is the ability to adapt to different environments. Until you see an investor adapt to something new, there’s a good chance that his real skill is being in the right place at the right time. Everyone is a long-term investor during bull markets. Can you keep your head on straight during bear markets? Adapt to a new world of low returns? Or higher interest rates? Adjust your strategy when it no longer works because so many other investors follow it?

The hardest thing is that things like interest rates, inflation, wars, regulations, and demographics work in long, 20-, 30-, even 50-year cycles. Few investors have track records that long, so we’re left with two inevitable truths: There are investors with great track records who probably just got lucky, and there are poor investors who probably would have looked like geniuses if they’d been born in a different era.

http://www.fool.com/investing/general/2015/09/04/the-long-road-of-proving-yourself-as-an-investor.aspx

Tags: cash flow model over earnings model, cash return on invested capital model, discount to book value model, dividend model, expert investor is the ability to adapt to different environments, growth companies, high dividend paying companies, investing expertise, investing strategies, investment wisdom, long term investing, only time separates skill versus luck in investing, true investing skill is outperformance up when the world changes, true investing skills is adapting and thriving in different market environments

Oxstones Investment Club™

Oxstones Investment Club™